7/6/2021

·Enable high contrast reading

The Miracle at the Mirror

Of course I’m late to my first haircut in eight months, and my tardiness requires a different stylist than the one I originally scheduled with. This waste of other people’s time would have mortified me prior to becoming Colson’s mom, but at this moment I am too fragile to care.

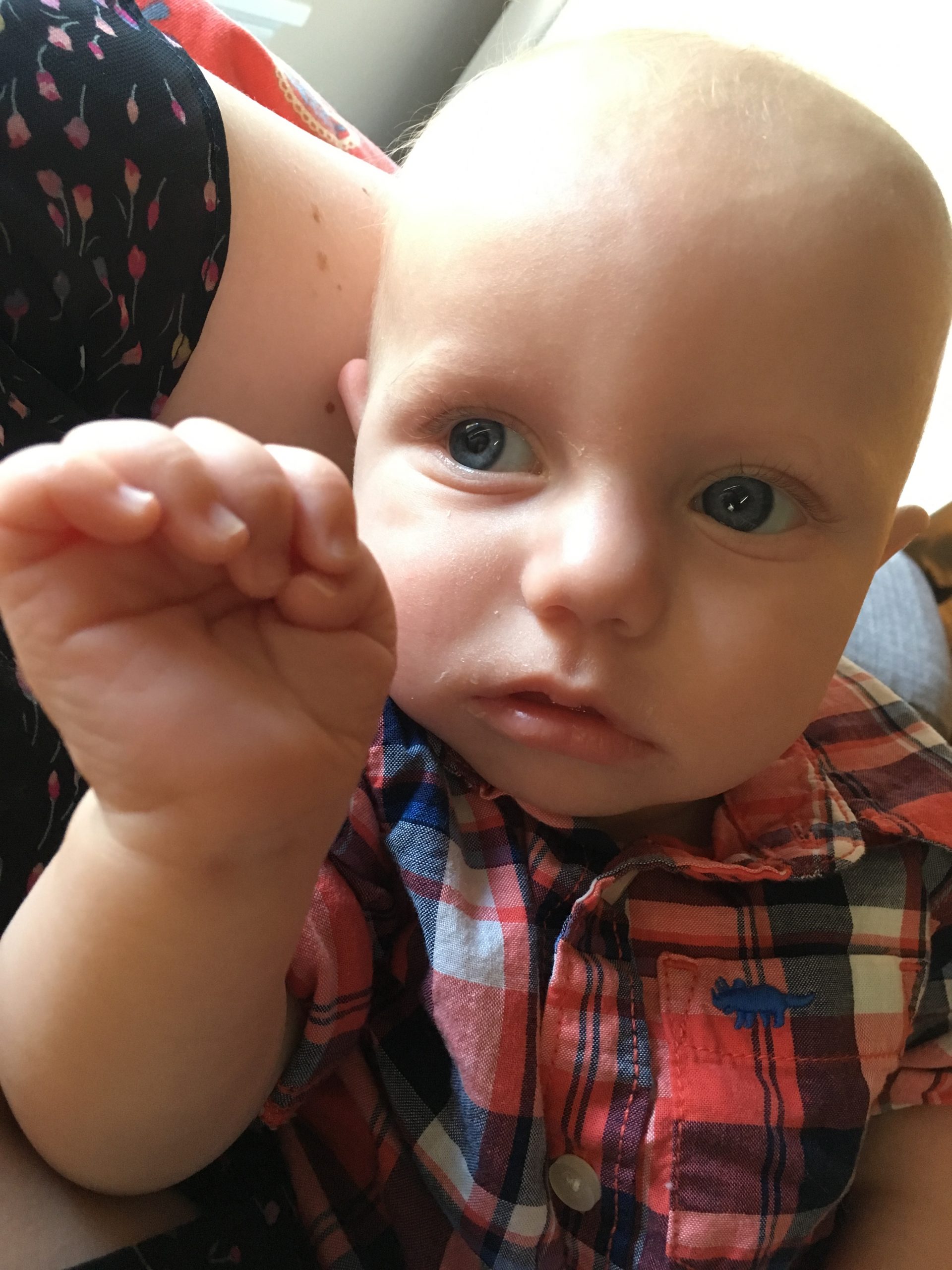

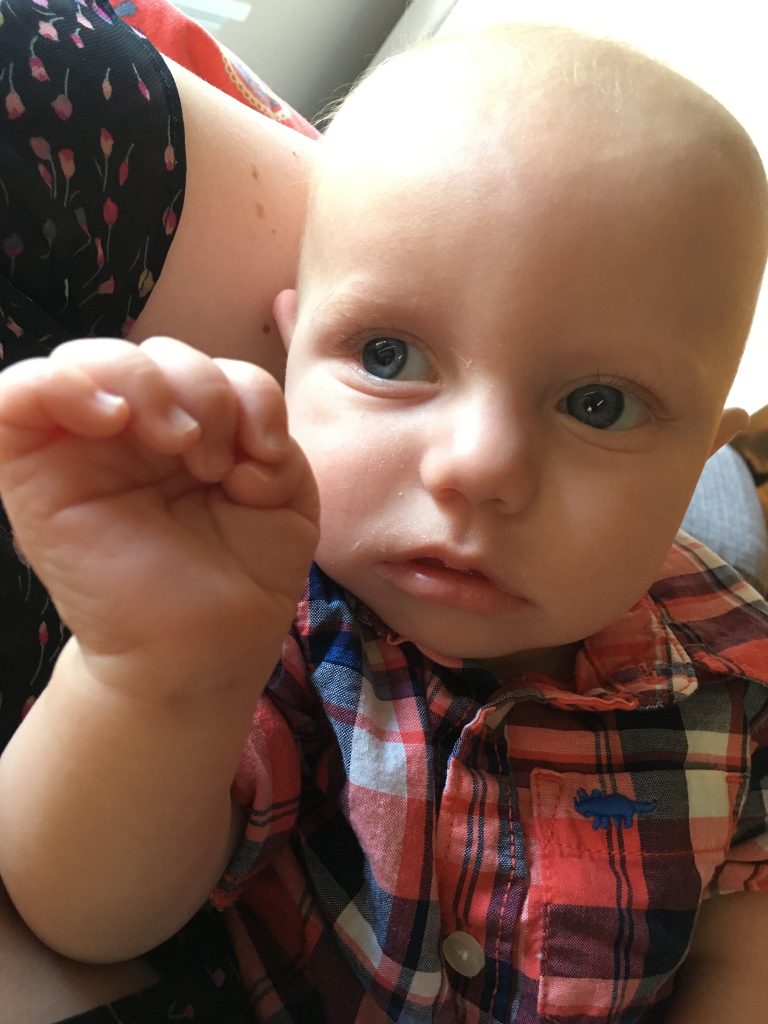

I show up to Rudy’s Barbershop for some perfunctory self-care on a sunny day in July 2017, still shaking from the aftershocks of my afternoon. A visit with Colson’s optometrist earlier in the day confirmed what his daddy and I already suspected: his mitochondrial disease has caused his optic nerves to atrophy. Colson is blind at eight months old. We had warily watched his wandering eyes for months – unable to get him to focus on bright objects or silly faces or screens. I perversely hoped that what we saw in his unseeing was cortical visual impairment – a condition in which the brain does not translate visual stimulus, but the input is still getting there. In the absence of understanding anything about Colson’s conscious experience due to his intellectual disabilities, I desperately wanted the chance for his brain to experience beauty through sight – even if his mind could not make sense of it. And now I know that he will spend the rest of his bright life in darkness. The weight of this knowledge threatens to immobilize me, but as a ‘medical mama’, I’ve gotten good at forcing myself forward through heartbreak.

I show up to Rudy’s Barbershop for some perfunctory self-care on a sunny day in July 2017, still shaking from the aftershocks of my afternoon. A visit with Colson’s optometrist earlier in the day confirmed what his daddy and I already suspected: his mitochondrial disease has caused his optic nerves to atrophy. Colson is blind at eight months old. We had warily watched his wandering eyes for months – unable to get him to focus on bright objects or silly faces or screens. I perversely hoped that what we saw in his unseeing was cortical visual impairment – a condition in which the brain does not translate visual stimulus, but the input is still getting there. In the absence of understanding anything about Colson’s conscious experience due to his intellectual disabilities, I desperately wanted the chance for his brain to experience beauty through sight – even if his mind could not make sense of it. And now I know that he will spend the rest of his bright life in darkness. The weight of this knowledge threatens to immobilize me, but as a ‘medical mama’, I’ve gotten good at forcing myself forward through heartbreak.

The new-to-me stylist, Meghan, washes my hair and guides me to her chair, which I promptly slump into with all of the heaviness I feel. My soaking mane frames my face, which is puffy from crying but also cavernous under my eyes from lack of sleep. I look and feel like a bedraggled cat that just crawled out of a storm pipe. A perfect time for small talk. Meghan asks, “So, what do you do?” and I cobble together my current truth. “Well, I used to work as a project manager for programs with public libraries, and I loved it. But my son was born sick so now I am his primary caregiver.”

I waited for the quick, discomforted change of subject that I had come to expect when I lobbed this tough truth at strangers. Meghan merely nodded: slowly, gently, knowingly. Not running away from my truth, she moved even closer to it and asked, “May I ask what your son’s illness is called?“

“May you?!” my inner voice exclaimed. “Of course you may! It’s all I’ve been thinking about for the past eight months!” Her nodding continued as I told her that Colson was born with mitochondrial disease, so the parts of his cells that turn food into energy don’t work well and his entire body is compromised. Her nodding picked up pace. I’ve never loved a bobbing neck more. After a momentary silence that told me she had been genuinely listening, Meghan reverently said, “I know what that is. My nephew Jackson had that.” And here, in this barbershop chair, occurs the first miracle of my life as Colson’s mom. I met a person who knew about my son’s merciless disease.

I had yet to meet a family impacted by mitochondrial disease, let alone understand how it unfolded for them. Meghan told me that Jackson had been born with mitochondrial disease and passed away from its complications just one day before his third birthday. Meghan shared a bit about her experience as witness to the tremendous effort of love and logistics that her brother and sister-in-law undertook to care for Jackson. She told me about the Mitochondrial Research Guild at our local children’s hospital, where I subsequently found stories of local families who loved children like mine. Meghan told me about the memorial wall at Seattle Children’s Hospital, where Jackson’s name was added after his death. I took Colson to visit that wall several times over the course of his life, where I would touch Jackson’s name and thank his story for finding its way to ours. Colson’s name is now on that wall.

This miracle at the mirror energized me to connect to the mitochondrial disease community. I connected with Jackson’s generous mom, Michelle, who, along with Jackson’s dad Zach, have graciously allowed me to share this story. Through our local guild, I discovered the national United Mitochondrial Disease Foundation (UMDF), where I now serve as a patient ambassador. While he was alive, we celebrated Colson’s life and shared his story through annual fundraising walks with UMDF. I was able to seek guidance from other families on things like tube feeding, mobility support and clinical research. I was able to offer my own wisdom and encouragement to new families, and I have made true friends through these networks. And, although Colson is now gone, these communities provide a place for our lived family experience to serve others.

This miracle at the mirror energized me to connect to the mitochondrial disease community. I connected with Jackson’s generous mom, Michelle, who, along with Jackson’s dad Zach, have graciously allowed me to share this story. Through our local guild, I discovered the national United Mitochondrial Disease Foundation (UMDF), where I now serve as a patient ambassador. While he was alive, we celebrated Colson’s life and shared his story through annual fundraising walks with UMDF. I was able to seek guidance from other families on things like tube feeding, mobility support and clinical research. I was able to offer my own wisdom and encouragement to new families, and I have made true friends through these networks. And, although Colson is now gone, these communities provide a place for our lived family experience to serve others.

At the end of June, I participated on a UMDF panel about our experience accessing and using cannabis to treat Colson’s seizures. (Colson’s medical marijuana ID card is one of my favorite things in this world.) I am currently communicating with our local guild about the possibility of getting his disease trajectory published as a case study in the medical literature. And, because we cared for Colson at the complex crossroads of chronic illness and disability, I am working to educate myself on other intersectional experiences through platforms such as the Disability Visibility Project, so that what I share through our singular story becomes expansive rather than reductive.

Through Meghan, I met a person who would lead me to my people. People with lived experiences of mitochondrial disease. People who had somehow survived the agony it wreaks. People who would ultimately make me feel connected and whole, rather than isolated and broken. We are lucky that we had a name for Colson’s disease, although we had no roadmap. A name led us to a network of support. For those who may be undiagnosed, or so extremely rare that a name does not yet exist, the National Organization of Rare Disorders is an excellent starting point for community-building. And, of course, you have a community here through Courageous Parents Network.

Through Meghan, I met a person who would lead me to my people. People with lived experiences of mitochondrial disease. People who had somehow survived the agony it wreaks. People who would ultimately make me feel connected and whole, rather than isolated and broken. We are lucky that we had a name for Colson’s disease, although we had no roadmap. A name led us to a network of support. For those who may be undiagnosed, or so extremely rare that a name does not yet exist, the National Organization of Rare Disorders is an excellent starting point for community-building. And, of course, you have a community here through Courageous Parents Network.

Being a complex caregiver is tremendously isolating, but please know that you are not alone.

Liz Morris loves exploring complex questions. Her professional experiences in project management, librarianship, and community development prepared her well for her favorite role as mom to Colson. Colson, impacted by mitochondrial disease since birth, inspired Liz to face the complicated aspects of his life through writing and advocacy. Liz serves as a family advisor at Seattle Children’s Hospital, and is a volunteer ambassador for the United Mitochondrial Disease Foundation. She is committed to helping families find the information they need to help them live well in the face of life-limiting illness. You can find Liz on Instagram @mrsliz.morris

Liz Morris loves exploring complex questions. Her professional experiences in project management, librarianship, and community development prepared her well for her favorite role as mom to Colson. Colson, impacted by mitochondrial disease since birth, inspired Liz to face the complicated aspects of his life through writing and advocacy. Liz serves as a family advisor at Seattle Children’s Hospital, and is a volunteer ambassador for the United Mitochondrial Disease Foundation. She is committed to helping families find the information they need to help them live well in the face of life-limiting illness. You can find Liz on Instagram @mrsliz.morris