7/11/2021

·Enable high contrast reading

The Trials of Clinical Trials - Part 2

CPN is honored that the Byers family has agreed to share and reflect on their experience of having their son Will participate in two very different clinical trials. In Part One, Will’s mother, Valerie talked about their decision to enroll Will, and the screening process.

The Challenge

When we said “yes” to our son, Will, participating in a clinical trial for Sanfilippo Syndrome, we thought we understood what we had chosen. We had read through the informed consent, asked questions, consulted with medical professionals, and reached out to other families. In our situation, we decided that the known risk of the untreated condition was greater than the potential risk associated with being part of the clinical trial. We also felt a responsibility to the Sanfilippo community. Through Will’s participation, we would be helping push the research forward, possibly to a feasible treatment, that would help all the other children who couldn’t be in this trial.

When we said “yes” to our son, Will, participating in a clinical trial for Sanfilippo Syndrome, we thought we understood what we had chosen. We had read through the informed consent, asked questions, consulted with medical professionals, and reached out to other families. In our situation, we decided that the known risk of the untreated condition was greater than the potential risk associated with being part of the clinical trial. We also felt a responsibility to the Sanfilippo community. Through Will’s participation, we would be helping push the research forward, possibly to a feasible treatment, that would help all the other children who couldn’t be in this trial.

However, the reality of being a part of a clinical trial is that you can never understand what you are choosing until you have lived it. The full clinical trial experience is not something for which you can be fully prepared, especially when it’s a clinical trial for a rare condition. There are unique practical and emotional challenges involved. There are sacrifices.

Trials for rare conditions often only occur in select locations due to the limited patient population and the cost that goes into procuring trial sites. This places the burden of either routine traveling or even relocation on a family, taking them away from their usual support networks. For us, Will’s trial required biweekly trips to Minnesota from Texas. Every other Wednesday, Will and I would pack our bags, head to the airport, eat lunch, fly north, pick up a rental car, pick up dinner, and check into our hotel. The next morning, we would eat breakfast, pack up, check-out, and head to the hospital for a full day. At roughly dinner time, we’d be discharged, head to the airport, return the rental car, find dinner at the airport, and fly back home in time to get Will to bed for school on Friday. It was exhausting. Caring for a child with special needs is taxing in normal conditions, but to do it when traveling and by oneself is overwhelming.

Trials for rare conditions often only occur in select locations due to the limited patient population and the cost that goes into procuring trial sites. This places the burden of either routine traveling or even relocation on a family, taking them away from their usual support networks. For us, Will’s trial required biweekly trips to Minnesota from Texas. Every other Wednesday, Will and I would pack our bags, head to the airport, eat lunch, fly north, pick up a rental car, pick up dinner, and check into our hotel. The next morning, we would eat breakfast, pack up, check-out, and head to the hospital for a full day. At roughly dinner time, we’d be discharged, head to the airport, return the rental car, find dinner at the airport, and fly back home in time to get Will to bed for school on Friday. It was exhausting. Caring for a child with special needs is taxing in normal conditions, but to do it when traveling and by oneself is overwhelming.

Because of the effects of Sanfilippo on executive processes, Will never had a sense of “danger” and had no impulse control. For his safety, I could never leave him alone, not even for me to go to the bathroom or to take a shower. I remember intentionally dehydrating myself until we got to the hospital, where I could have a nurse stay with him for brief periods so I could use the restroom. But there was no other option. My husband could not take off from work the amount of time necessary to accompany me and my friends and family had jobs and children of their own of which to take care. For our quarterly week-long trips, I was able to secure help, but for our 2-day adventures, Will and I were on our own.

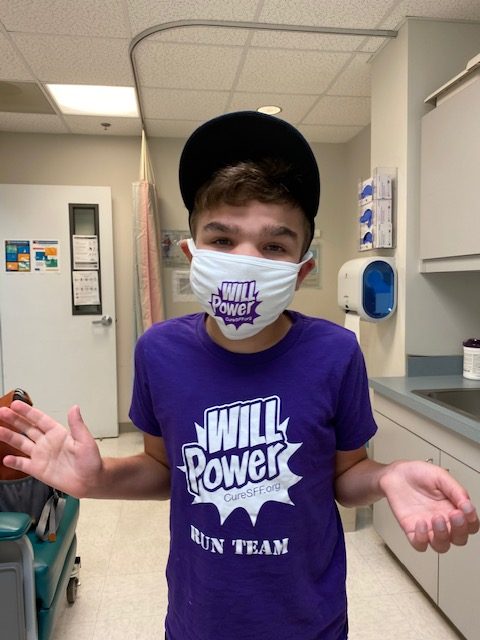

But being on our own was not necessarily a bad thing. It was a special time for he and I to be together. I cherish many of our memories as we worked to make Minnesota more like a home-away-from-home than just a trial location. We made friends with employees at the car rental desk, at our hotel, and at the restaurants we frequented. Airport staff knew Will by name, recognizing him quickly due to our purple WILLPower sweatshirts and his signature traveling hat, a fedora. Hospital staff knew exactly when to turn Paw Patrol or Daniel Tiger on the TV to prevent Will from becoming fussy during procedures. We met other families in our trial and supported each other, as we were the only ones who could really understand what we were all facing. These little things helped lighten the load.

But being on our own was not necessarily a bad thing. It was a special time for he and I to be together. I cherish many of our memories as we worked to make Minnesota more like a home-away-from-home than just a trial location. We made friends with employees at the car rental desk, at our hotel, and at the restaurants we frequented. Airport staff knew Will by name, recognizing him quickly due to our purple WILLPower sweatshirts and his signature traveling hat, a fedora. Hospital staff knew exactly when to turn Paw Patrol or Daniel Tiger on the TV to prevent Will from becoming fussy during procedures. We met other families in our trial and supported each other, as we were the only ones who could really understand what we were all facing. These little things helped lighten the load.

However, these bright spots didn’t erase the other challenges we faced. Being part of the clinical trial meant that even our home life was a data set. Any scrape, bump, doctor visit, or medication had to be reported. Also, due to the clinical trial time commitment, I was unable to work, meaning our family budget needed adjusted to account for being based on a single income for the foreseeable future. It also meant that we would have to continue to procure regular childcare for our toddler daughter so that I could travel with Will and so my husband could continue to work to provide for our family.

These practical challenges led to emotional costs. We were already dealing with the emotional costs of the disease itself, but the trial also added anxiety as we worried whether the treatment was helping Will or not. Traveling added stress to a marriage that was already feeling the weight of having a child with a terminal diagnosis. Leaving my daughter every other week was very difficult and emotional for me as a mother and losing my career-focus was very difficult and emotional for me as a professional. Our family would have benefited from counseling, but time and money were now stretched even tighter due to trial participation.

We worked together, we rallied, and we did all that was required of us. We were faithful to our agreement to the trial and felt that as long as we continued to put in the work, we were giving Will his best shot at a high quality of life.

And then our trial was cancelled.

The Cancellation

I remember the day so well. Will was 2 years into the 3-year enzyme replacement trial for Sanfilippo Syndrome and I was at the airport, for once not bound for Minnesota. Instead, I was alone and heading to visit a dear friend in Illinois. It was to be a much needed and much anticipated weekend of respite for me. It felt like a huge splurge, this gift of a weekend away from caregiving duties. However, a caregiver can’t ever truly set aside the job of caregiving. Walking through the airport by myself was disorienting and I found myself having small moments of panic when I forgot that I wasn’t traveling with Will, frantically glancing around for him before remembering that I was alone. My thoughts were so used to being caught up in his care that I couldn’t comprehend the privilege of drinking coffee while it was still hot or being able to go to the bathroom by myself.

As I told myself to focus, to take in this gift and allow myself to rest, my phone rang.

Although we had read a press release earlier in the year telling us that the trial sponsor wasn’t looking to expand Will’s trial due to financial constraints, the news delivered in that call was completely unexpected. We had seen the promising data that had been presented at conferences and we had also seen the promising data in our own son. His regression had slowed and his quality of life was high. An expensive treatment, it didn’t come as a surprise that they weren’t adding in more participants, but we had been assured Will would complete the 3-year treatment period. We had even been given the schedule for the start of our third year and had begun work on making all the arrangements that were necessitated by that. So, I was completely caught off guard when I answered the call from another parent from the trial telling me that the trial had been cancelled because the sponsoring company said it wasn’t meeting its goal of stopping the cognitive regression.

Although we had read a press release earlier in the year telling us that the trial sponsor wasn’t looking to expand Will’s trial due to financial constraints, the news delivered in that call was completely unexpected. We had seen the promising data that had been presented at conferences and we had also seen the promising data in our own son. His regression had slowed and his quality of life was high. An expensive treatment, it didn’t come as a surprise that they weren’t adding in more participants, but we had been assured Will would complete the 3-year treatment period. We had even been given the schedule for the start of our third year and had begun work on making all the arrangements that were necessitated by that. So, I was completely caught off guard when I answered the call from another parent from the trial telling me that the trial had been cancelled because the sponsoring company said it wasn’t meeting its goal of stopping the cognitive regression.

I recall feeling as if I was underwater. Shapes moved more slowly around me and sounds were muffled. I think I accidentally knocked into a woman as I walked and, as she yelled at me, I gazed at her without comprehension of what she was saying. I called our clinical trial nurse for confirmation that the trial was actually being ended and, when I had it, I called my husband with a voice filled with panicked tears. “What are we going to do?” I asked, “They are taking it away from him. He’s going to die.”

I was near hysterics, uncomprehending of what was happening and feeling like I was in a dreamlike sequence. I felt just as bad, if not worse, than our diagnosis day. Diagnosis day robbed us of our innocence, but the trial cancellation threatened to rob us of our hope. We knew that losing this treatment was the end of the road for Will. Now considered “damaged goods” by the research community due to having already been part of an experimental treatment, we were told he would never be eligible for a clinical trial again. The possibility of the trial being cancelled prior to the 3-year mark when there hadn’t been any safety issues hadn’t even crossed our minds. We felt abandoned.

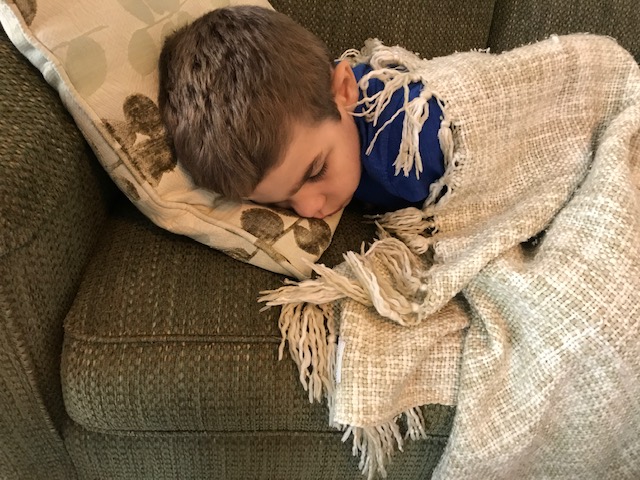

We bore it as well as we could. We had rare disease advocates fight for continued access to the remaining drug and were denied by the pharmaceutical company. We watched our son go through hellacious withdrawal symptoms after being made to quit the infusion cold-turkey as they refused even our request to wean the participating children slowly off of the treatment. Will stopped walking and talking and started screaming in agitation and pain. The clinical trial team, which had required us to report any bump or bruise Will experienced over the past two years, wouldn’t even take our calls or help us navigate the withdrawal period.

We bore it as well as we could. We had rare disease advocates fight for continued access to the remaining drug and were denied by the pharmaceutical company. We watched our son go through hellacious withdrawal symptoms after being made to quit the infusion cold-turkey as they refused even our request to wean the participating children slowly off of the treatment. Will stopped walking and talking and started screaming in agitation and pain. The clinical trial team, which had required us to report any bump or bruise Will experienced over the past two years, wouldn’t even take our calls or help us navigate the withdrawal period.

It took a month but, thankfully, Will started to rebound. His body began to remember how to work on its own again without the regular enzyme infusions it had come to rely on for 2 years. But even then, we continued to feel betrayed by our clinical trial experience. For 2 years, we had allowed our son to be poked, prodded, anesthetized, and examined. He’d endured blood draws and PICC line placements, MRIs and spinal taps. As parents, we’d filled out form after form, assessment after assessment. We’d taken time away from our families and from our work. Then, not only was the clinical trial treatment suddenly taken away, but the trial sponsor refused to share any of the valuable data they had gathered. That shattered us even further. We had chosen to be part of the trial, not only for Will’s benefit, but for the benefit of the Sanfilippo patient community. We knew the data would be kept private during the trial, but we had incorrectly assumed the data would be published at the end of the trial, regardless of the results. Any data collected from the trial had the potential to be beneficial to other research studies but since the company owned data, they didn’t have to share it. It was like a slap in the face.

Cancelled trials and the lack of data sharing can have a strong impact on rare disease research: They erode the faith the rare disease community has in the clinical trial process. Families, willing to sacrifice anything to be part of the trial, do not feel valued for their sacrifice. When it feels as though the research community does not have our loved ones’ best interests at heart, why should we subject ourselves or our children to the substantial risks and burdens of clinical trials? And yet without clinical trials, how do we fulfill our promise to do whatever necessary to give our loved ones the quality of the life they deserve? It can make families feel like they are between a rock and a hard place and alone in our decision making.

Cancelled trials and the lack of data sharing can have a strong impact on rare disease research: They erode the faith the rare disease community has in the clinical trial process. Families, willing to sacrifice anything to be part of the trial, do not feel valued for their sacrifice. When it feels as though the research community does not have our loved ones’ best interests at heart, why should we subject ourselves or our children to the substantial risks and burdens of clinical trials? And yet without clinical trials, how do we fulfill our promise to do whatever necessary to give our loved ones the quality of the life they deserve? It can make families feel like they are between a rock and a hard place and alone in our decision making.

The Change

Following the cancellation of Will’s trial, we continued our efforts to raise the profile of Sanfilippo Syndrome. However, due to our recent clinical trial experience, we had new advocacy avenues we wanted to explore and support, changes we wanted to see made. Recognizing that there was a disconnect between the clinical trial endpoints prioritized by pharmaceutical companies and the clinical trial endpoints prioritized by rare disease patients and their caregivers, we worked with the Cure Sanfilippo Foundation as they developed their Caregiver Preference Study to present to the FDA. This study, based on responses from actual caregivers, highlighted the need to include clinical trial endpoints that were based around quality of life improvements that were important to families. The goal is now for any proposed clinical trial for Sanfilippo Syndrome to include these factors as significant endpoints to help determine the success level of a potential treatment. We further worked with the Foundation to support other clinical trial changes, including open data sharing, increased aftercare following a trial’s completion, and more caregiver input and involvement throughout the clinical trial process.

The Cure Sanfilippo Foundation prioritized these clinical trial recommendations when they developed and funded their own quality of life clinical trial, the Open-label Study of Anakinra in MPS III. Although not designated as a potential “cure” for Sanfilippo Syndrome, this study was designed with goal of mitigating some of the symptoms of Sanfilippo in order to improve quality of life for both the patients and the caregivers. The design of the study also took caregiver burden into account and wrote in specific protocols to make participating in the trial as family-friendly as possible. This trial is an important model demonstrating how research and family priorities do not have to be in conflict with one another and how, by including patient and caregiver voices in clinical trial development, trial sponsosr can devise treatment options that better meet the needs of patients while also building bridges for continued trust and cooperation within rare disease communities.

The Cure Sanfilippo Foundation prioritized these clinical trial recommendations when they developed and funded their own quality of life clinical trial, the Open-label Study of Anakinra in MPS III. Although not designated as a potential “cure” for Sanfilippo Syndrome, this study was designed with goal of mitigating some of the symptoms of Sanfilippo in order to improve quality of life for both the patients and the caregivers. The design of the study also took caregiver burden into account and wrote in specific protocols to make participating in the trial as family-friendly as possible. This trial is an important model demonstrating how research and family priorities do not have to be in conflict with one another and how, by including patient and caregiver voices in clinical trial development, trial sponsosr can devise treatment options that better meet the needs of patients while also building bridges for continued trust and cooperation within rare disease communities.

The most important aspect of this new trial for us? It didn’t exclude children who had been in clinical trials in the past from applying to participate. And so, again, we had another tough decision to make. Knowing what we now knew about the clinical trial process, would we attempt to do it again? Our questions this time were much more focused, making sure to assume nothing and get every detail necessary to make an informed decision. We now DID know what we were getting ourselves into and wanted to make sure all the concerns we’d had in the past were being addressed. Because this trial had been developed with caregiver preferences and support in mind, we felt much more comfortable with applying for screening.

And so, in 2020, Will again donned his purple WILLPower shirt and traveling hat to this time head to California, where he was screened for another clinical trial. He was accepted and began his second clinical trial for Sanfilippo Syndrome in summer of 2020. This is another previously inconceivable phenomenon in the rare disease world: the opportunity for a second trial. But hopefully, as we continue to elevate the importance of quality of life benefits in rare disease research and educate companies on how to best work with rare disease patients and their families, this concept will become less unusual, giving more people the chance fulfill their promise to do anything they can to give their loved one more good days.

And so, in 2020, Will again donned his purple WILLPower shirt and traveling hat to this time head to California, where he was screened for another clinical trial. He was accepted and began his second clinical trial for Sanfilippo Syndrome in summer of 2020. This is another previously inconceivable phenomenon in the rare disease world: the opportunity for a second trial. But hopefully, as we continue to elevate the importance of quality of life benefits in rare disease research and educate companies on how to best work with rare disease patients and their families, this concept will become less unusual, giving more people the chance fulfill their promise to do anything they can to give their loved one more good days.